Shared from blog.hoosiertimes.com

Let me begin with two disclaimers.

- I am angry. I am angry that so many of the people that I have worked with and whom I have seen in my visits to schools around the country are having their work and commitment demeaned and depreciated. But I’ve learned that anger is secondary emotion and there is a root cause for that anger. For me it is frustration. I am frustrated with our nation’s continued unwillingness to devote sufficient time to the analysis of a problem, pouring incredible resources to the wrong thing and then seeking scapegoats when the solutions (to the wrong problem) are unsuccessful;

- I am not a social activist. I’m not a political organizer. My only attempts at such activity involved trying to organize the teachers at the private school where I began my teaching career. I was invited to look elsewhere for employment. I’m looking to have a better end this time around.

So this post is a follow-up to the recent” what can I do” blog. It is not a cookbook on political organizing. It’s about changing roles. It’s about changing roles because I believe that our ability and willingness to effectively organize and affect our futures are directly related to the role that we see for ourselves.

As teachers we have experienced a unique form of career exploration and training. We are most likely the only profession in which the practitioners had at least 16 years to observe the career that they eventually selected. What is remarkable about this is that, while much is written about the quality of teacher preparation programs, the impact of postgraduate studies, and the value of locally offered professional development, substantial research exists that indicates that these have not been the determining factors in how teachers teach and how they see themselves.

The most formative factor turns out to be how they were taught. That is to say that we have been trained not only in how we teach but also how to see ourselves by the experiences we have had as students in school and our observations about how teachers behaved and saw themselves.

The point here is that the vast majority of teachers have formed their notions about teaching from experiences that they had at least 10-20 years before they entered the profession. As Kieran Egan expressed in his book, The Educated Mind – How Cognitive Tools Shape Our Understanding, these lessons were learned during a time when one of the primary goals of the American education system was the homogenization of our society – the intentional efforts to protect and transmit the societal norms of the time.

The success of this mission was measured by behavior and the compliance with the established norms. We have both been trained in and charged with insuring compliance. It has become an accepted part of the DNA of teachers in our country.

The world has changed (you may have read something about this); however, we have maintained the roles and role expectations that were formed in another time and in a different context. That is to say, our default response when confronted with confusing and often uncomfortable data is… compliance.

Since the publication of A Nation At Risk in 1983 the citizens of our country have been fed a steady narrative of failure. During that same time we have witnessed the ideological commitment to this narrative and a series of “reforms” designed by such great educational thinkers as the National Governors” Association and funded by an increasing number of “education-minded” philanthropists.

NOTE: For an interesting and contrary analysis of the scholarship behind A Nation At Risk, you might like to read an article that appeared in EdWeek in August 2004, 20 years after the reports publication.

While in our faculty rooms and at teacher dominated social gatherings, you might hear frustration and anger at the unfairness of the current anti-school/anti-teacher narrative. As individuals, however, we have remained largely silent as the standards/assessments, test/punish direction of mandated programming continues and expands.

So?

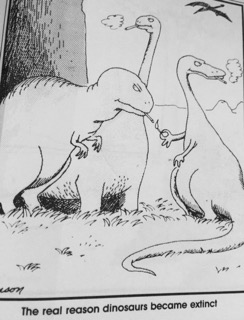

From Facebook

I believe it is critical that we cast off the role of quiet compliance. I believe it is time for us to recover the leadership of the direction of what happens to our kids in our schools. It is no longer enough to assume that paying our association dues and nodding our heads to the lobbying efforts of our national organizations will derail (or for the optimists, redirect) the direction of the last two decades.

So What Can I Do?

We old folks can remember a film from 1967, The Graduate. The film contained a memorable moment when Dustin Hoffman received a one-word piece of advice for his career choice and future – “Plastics”. After a seemingly endless pause, the advice giver explained that there was a great future in plastics.

The 2016 version of that one-word piece of advice for us is – “alliances”.

I included above a photo from the Egyptian Revolution of 2011. I included this to remind us of the manner in which a grass roots movement exploited 21st Century communications tools, like Twitter and Facebook, to inform, to encourage, to mobilize and, yes, to coordinate the efforts to raise awareness and force change.

One of the ironies and untapped strengths of our situation is that, while the politicians and business leaders have committed huge amounts of resources to demeaning teachers and teaching, to the narrative of schools as “failure factories”, to the “wonders” of portfolio school systems (read privatized), the majority of Americans surveyed continue to trust the teachers of their children.

We need to build alliances on this trust and help these alliances change the narrative of public education and teaching. We need to begin with the parents in our classrooms. We need to bring information to them, in easy to digest format – blogs, video clip, infographics, etc.

As I mentioned in the first post on this topic, Jan Ressger’s report on the efforts of the folks in Vermont gives us great talking points to begin our conversation. Diane Ravitch and Sir Ken Robinson add wonderful insight and direction as well.

We need to bring this same information to local and regional PTA/PTO’s.

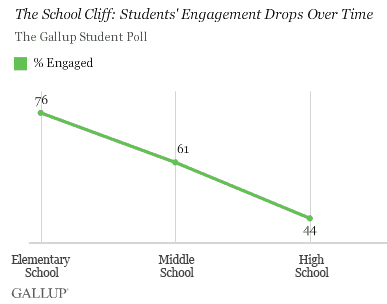

We need to highlight and emphasize the real consequences that our kids are experiencing in this reform age.

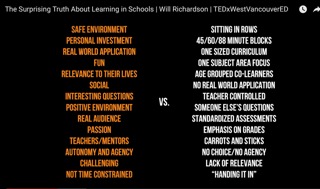

As threatened as we might be by the unfairness and lack of validity of test-based teacher evaluations, we need to separate that issue from the harm done to our children by the test score driven, one-dimension measurement of kid success and the accompanying loss if attention to the development of multiple talents.

We need to help interested parents prepare to talk with board members about planned or real reductions in arts programming, flack of focus on life/soft skill development, one-size fits all curricula, etc.

But most importantly we need to learn from the organizing lessons of the Egyptian Revolution, Occupy Wallstreet, and, most recently, the Opt Out movement to leverage social media potential into an intentional effort to prevent the continued chasing of the wrong thing.

We need to step away from the traditional role of teachers – a role that emphasized isolation and independence – to one that utilizes the demonstrated strength of alliances. We need to form alliances with colleagues both in our schools and via social media in other schools. We need to form alliances with parents to help them make their voices heard. We need to form alliances with members of our local boards of education and to help them form similar alliances with their counterparts in other districts.

A final disclaimer. This is not about the preservation of the status quo. This is about eliminating the distraction caused by a thoughtless and ill-considered reform agendas that focus on moving backwards into the future. This is about gaining the opportunity to re-imagine education, learning, and the place of our schools in that process.

If you would like to continue this conversation about concrete actions and alliance building opportunities, please add your voice to the comments.

You may recall that a week or so ago, I took my own advice and offered testimony at a public hearing organized and hosted by the state Department of Education. This event was a part of a requirement for the state’s submission of a plan for the recently passed ESSA legislation.

You may recall that a week or so ago, I took my own advice and offered testimony at a public hearing organized and hosted by the state Department of Education. This event was a part of a requirement for the state’s submission of a plan for the recently passed ESSA legislation.

I recall reading an observation by

I recall reading an observation by