“There are two orders of things: There is the seen order unfolding in front of us every day on our streets and in the news…We call this order of things reality. This is “the way things are.” It’s all we can see because it’s all we’ve ever seen. Yet something inside us rejects it. We know instinctively: This is not the intended order of things. This is not how things are meant to be. We know that there is a better, truer, wilder way. That better way is the unseen order inside us. It is the vision we carry in our imagination about a truer, more beautiful world—”

Glennon Doyle – Untamed

Whether you’re a parent, a relatively new teacher (like my granddaughter in Houston) or are considered a teaching “veteran”, you have probably felt what Glennon Doyle describes at the beginning of her book, Untamed. If you nodded your head to the phrase “This is not how things were meant to be”, this post is or you. It is based on the beliefs that trying to do the wrong thing better is frustrating and that we’ve been spending too much time doing that.

Several years ago, I joined Modern Learners, an on-line community focusing on the need to transform the frustrating experiences that our kids and their teachers were having in many schools. My decision to join the group was in response to my need to find a way, after a number of failed attempts, to actually retire. The funny part of this is that this decision actually worked. I no longer worked… well, at least not for money. Ironically, as a result of that decision, I’ve actually worked more and harder than in any of my previous retirement attempts.

But, more importantly, as a result of my interactions with others within the Modern Learners community, I connected with several other educators who shared my interest in changing the focus of education from what we’ll term “schooling” to learning… not the “learning” that is tested annually in most states, but the kind of learning that we experience when we’re exploring something that has engaged our minds and our hearts… the kind of learning that isn’t about credit for time spent in class or compliance with rules established more for adult convenience than for genuine learning.

The result of this connection was the formation of a group, called “the Four Amigos”.… a team of like-minded educators from here in the US and Canada interested in an exploration of how we might help teachers, school leaders, parents, and kids experience something more than “schooling”… something that had learning as its center.

Most often our conversations with folks interested in change quickly move to the issue of “how” to change my schools or my district. This paper will be different. It will focus on “how” but it will not be oriented towards whole school or whole district change. Simply put, we no longer believe that whole school or whole district or large system change is likely… even with the turmoil that has accompanied the need imposed by the pandemic to drastically alter our approach to schooling. With very few notable exceptions, the national response in both of the countries represented on our team has been to replicate, as closely as possible, schooling as we knew pre-pandemic.

You will note that, as you explore our suggestions, we have focused on the importance of word choice. Throughout the paper, you will see the word “learner” rather than the word “student”. This is deliberate . It reflects our experience that connects the word student with attending school and being exposed to all of the practices, policies, and procedures which are designed primarily around adult convenience and efficiency… all of the which is contrary to our belief that much learning of value takes place/can take place beyond the walls of the school. It is for this reason that we distinguish between learning and schooling. For the very same reason we urge you to begin your exploration of the ways in which our children (as well as adults) learn with your own personal exploration/answer to the question, “What is learning?”

Take a look at a modified version of Glennon Doyle’s words (bold, italics mine)…

“There are two orders of things: There is the seen order unfolding in front of us every day in our schools…We call this order of things reality. This is “the way things are.” It’s all we can see because it’s all we’ve ever seen. Yet something inside us rejects it. We know instinctively: This is not the intended order of things. This is not how things are meant to be. We know that there is a better, truer, wilder way. That better way is the unseen order inside us. It is the vision we carry in our imagination about a truer, more beautiful world—”

For some additional context, here are a few thoughts offered by Yong Zhao in his recent paper xxx “The Changes We Need: Education Post COVID-19”, Journal of Educational Change (2021)

“…the changes or innovations that occurred in the immediate days and weeks when COVID-19 struck are not necessarily the changes education needs to make in the face of massive societal changes in a post-COVID-19 world. By and large, the changes were more about addressing the immediate and urgent need of continuing schooling, teaching online, and finding creative ways to reach learners at home rather than using this opportunity to rethink education. While understandable in the short term, these changes will very likely be considered insubstantial for the long term.

Readiness Is Not a Moral Issue

Not everyone sees the world as Zhao does. For some of us school worked as learners and continues to work for us as teachers. As Doyle notes (above)…It’s all we can see because it’s all we’ve ever seen. Some nod their heads to Zhao’s words, but are overwhelmed by the mere act of preparing each day for to teach in ways we never envisioned and for which we were never trained. Yet others have imagined experiences that are very different and are waiting for opportunities or are ready to make opportunities. This paper is for you.

We urge you to begin your exploration of the ways in which our children (as well as adults) learn with your own personal exploration/answer to the question, “What is learning?”

Why an individual approach? What we’ve learned…

What we have learned in the years leading up to the pandemic and what has been reinforced by our pandemic experiences is that in education, like almost all institutions, change happens very slowly. Seeking and/expecting large scale institutional change is a recipe for disappointment. Our small team has collectively more than 40 years of experience working to improve schools, school districts, even state policy. We have learned this…

- Barring forced large-scale change mandates from either a state or the federal government, schooling will remain for kids and teachers essentially as it has been since the Gang of Ten laid out the curriculum and the grade level structure for schools in 1893…

- Meaningful change for our learners will take place one teacher or small group of teachers at a time. It will take place because someone sees a possibility. It will take place because some says, “Enough!”. Maybe that someone will be a teacher, maybe a school leader, maybe a parent. What they see may look different from place to place… maybe even from class to class.

This is a Guide

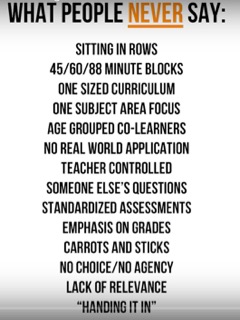

This paper is written as a guide for those who, individually or as a small group, can’t wait for change to catch up with their need to offer kids something different. It’s written for those who feel that learning is not about rigid standards, or curriculum organized in rigid content classes with little real-world connection or large-scale standardized assessments. Maybe it’s not even about age-determined grade levels or seat-time based credits.

It’s written for those whose know somewhere deep in their hearts that the purpose of education is both simple and clear.

It’s about helping our kids learn how to learn…not simply transferring information from our heads into their theirs; not simply getting them ready for the annual large-scale standardized assessment.

It’s about helping kids learn how to do… not simply repeat what they’ve read but to be able to produce, to make, to act.

It’s about helping kids learn how to be… not in the context of compliance to school rules but in the context of personal development, of emotional health, of growing into responsible, caring adults.

Moving on to “HOW” — Getting Started

Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?’

‘That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,’ said the Cat.”

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland (Carroll, 1960, p. 88)

The HOW process is begins with questions… BIG questions. My questions are “borrowed” from a commencement address offered by Dr. James Ryan to the 2016 graduates of the Harvard Grad School of Education. They’re the best questions I’ve found and I urge you to spend a fascinating few minutes with Dr. Ryan.

So, where do you want to get to? What matters to you?

Asking these questions regularly is a means of keeping focused… focused amid all the distractions that can muddy up our days and our intentions. If you have found that there is something about your life in school that seems “not the way things should be”, begin with Ryan’s 5th question… What matters to you? It’s your way to get to the heart of your beliefs and convictions. It’s a way of recapturing why you chose teaching as a career?

A sub-question to “what Matters” is “What do I believe?” What do I believe about kids? About learning? Surprisingly, when I’ve interviewed teachers in recent years, I learned that they had never been asked that question… not in the interview, not in any evaluation conferences. Taking time to answer these questions is a beginning to comparing what you are doing with what you believe is the right thing.

It cycles back to Ryan’s first question, “Wait! What?” Wait! I say I believe that all kids can learn and that kids should be active participants in their learning. But what am I doing that supports that belief? That seems to ignore that belief? How do the kids in my classes feel.

It is here that we can begin the next question, “I wonder if my kids would feel like active participants in their learning?” “I wonder what my classroom looks like and if it feels like I believe all kids can learn?”

A Sample exploration…

What would my class look like if I believe that…

- Learning should be learner focused, not teacher centered. The learner does the work of learning, not the teachers;

- Learning is personal because we learn through our unique, personal lens on the world. It relies on the individual’s prior knowledge and experiences;

- Learning should be personal, not “personalized” as in the current tech centered delivery system, but based on and organized around the personal interests and needs of learners;

- Learning always relies on the individual’s prior knowledge and experiences;

- Learning will frequently occur beyond the walls of the school;

- Learning is personalized when every voice in the room is heard and valued.

Whether you’re working on this alone or in a small group, don’t skimp on time here. Take some time. Write down what matters, write down what you believe about learning, write down what you feel about learning in your class.

For many, perhaps for the majority of those seeking change, these questions can be a great starting point. The common theme that runs through changes in the experiences of teachers and kids will be the clear and non-negotiable focus on learning… not on state test scores or test prep classes, but on learning… not on student control or compliance, but on learning… not transferring information from the teacher’s brain to the student’s, but on learning from the inside out… learning driven by student interests and teachers support/guidance in the exploration of these interests.

So where do I begin?

Since we’re looking at “Big Questions as our starting point, Yong Zhao offers 3 questions that are an excellent follow-up to the “what if/what would happen if” questions above.

He suggests that the three “big questions” that teachers who wish to see change will have to address are…

- The curriculum or What to teach?… a deep exploration of the current curriculum —

- Pedagogy or How to teach?… how will we move away from our traditional roles as the dispenser of information?

- Organization – Where and When to teach?

What does Zhao mean by each of these? How closely do these thoughts reflect your own thinking? If you had to start with one, which one would you begin with? Here’s some additional detail about each…

Curriculum – What To teach?

First, there’s a conflict between what we have been hearing and what have been teaching. While the specifics vary, the general agreement is that repetition, pattern-prediction and recognition, memorization, or any skills connected to collecting, storing, and retrieving information are in decline.

On the rise is a set of contemporary skills which includes creativity, curiosity, critical thinking, entrepreneurship, collaboration, communication, growth mindset, global competence, and a host of skills with different names (Duckworth and Yeager, 2015; Zhao et al. 2019).

…While helping learners develop basic practical skills is still needed, education should also be about development of humanity in citizens of local, national, and global societies. A new curriculum that responds to these needs must do a number of things.

First, it needs to help learners develop the new competencies for the new age (Barber et al. 2012; Wagner 2008, 2012; Wagner and Dintersmith 2016).

…The curriculum needs to focus more on developing learners’ capabilities instead of focusing only on ‘template’ content and knowledge. It needs to be concerned with learners’ social and emotional wellbeing as well. Also important is the gradual disappearance of school subjects such as history and physics for all learners. The content is still important, but it should be incorporated into competency-based curriculum.

Second, the new curriculum should allow personalization by learners (Basham et al. 2016; Zhao 2012b, 2018c; Zhao and Tavangar 2016). Although personalized learning has been used quite elusively in the literature, the predominant model of personalized learning has been computer-based programs that aim to adapt to learners’ needs (Pane et al. 2015). This model has shown promising results but true personalization comes from learners’ ability to develop their unique learning path- ways (Zhao 2018c; Zhao and Tavangar 2016).

…Enabling learners to co-develop part of the curriculum is not only necessary for them to become unique but also gives them the opportunity to exercise their right to self-determination, which is inalienable to all humans (Wehmeyer and Zhao 2020).

Third, it is important to consider the curriculum as evolving. Although system- level curriculum frameworks have to be developed, they must accommodate changes with time and contexts.

What to do with this?… As you reflect on Zhao’s thinking on “What To Teach” – use the following questions to assess possible actions…

- What are the things that I/we should keep “teaching”… e., what are the skills/dispositions that are leading to the learning I/we hope to see? Example: The ways which language is used to communicate.

- What are the things that I/we should stop “teaching” immediately…. i.e. what are the things/subjects that are keeping us from providing the kinds of experiences we want my/our kids (and ourselves) to have? Example: Disciplines disconnected from other areas of study.

- What are the things that we should I/we start “teaching” doing immediately… e., What are the experiences that my/our kids need to have which are currently unavailable to them? Example: How to converse and use empathy in the process.

Pedagogy – How To Teach

First, learners are unique and have individual interests that may not align well with the content they are collectively supposed to learn in the classroom. Teachers have been encouraged to pursue classroom differentiation (Tomlinson 2014) and learners have been encouraged to play a more active role in defining their learning and learning environments in collaboration with teachers (Zhao 2018c).

Second, the recent movement toward personalized learning (Kallick and Zmuda 2017; Kallio and Halverson 2020) needs learners to become more active in understanding and charting their learning pathways.

Learners should exercise self-determination as members of the school community (Zhao 2018c). The entire school is composed of adults and learners, but learners are the reason for existence of schools. Thus, schools and everything in the school environment should incorporate and serve the learners. Yet most schools do not have policies and processes that enable learners to participate in making decisions about the school—the environment, the rules and regulations, the curriculum, the assessment, and the adults in the school. Schools need to create these conditions through empowering learners to have a genuine voice in part of how they operate, if not in its entirety.

Direct instruction should be cast away for its “unproductive successes” or short-term successes but long term damages (Bona- witza et al. 2011; Buchsbauma et al. 2011; Kapur 2014, 2016; Zhao 2018d). In its place should be new models of teaching and learning. The new models can have different formats and names but they should be student-centered, inquiry-based, authentic, and purposeful. New forms of pedagogy should focus on student-initiated explorations of solutions to authentic and significant problems. They should help learners develop abilities to handle the unknown and uncertain instead of requiring memorization of known solutions to known problems.

What to do with this?… As you reflect on Zhao’s thinking on “How to Teach” – use the following questions to assess possible actions.

- What are the practices that I/we should keep?… Example: Learners working collaboratively

- What are the practices that I/we should stop immediately? Example: Calling on first student to raise his/her hand.

- What should I/we start doing immediately? Example: Engage learners determining what is to be explored.

Organization – where and when to teach?

Moving teaching online is significant. It ultimately changed one of the most important unwritten school rules: all learners must be in one location for education to take place. The typical place of learning has been the classroom in a school and the learning time has been typically confined to classes.

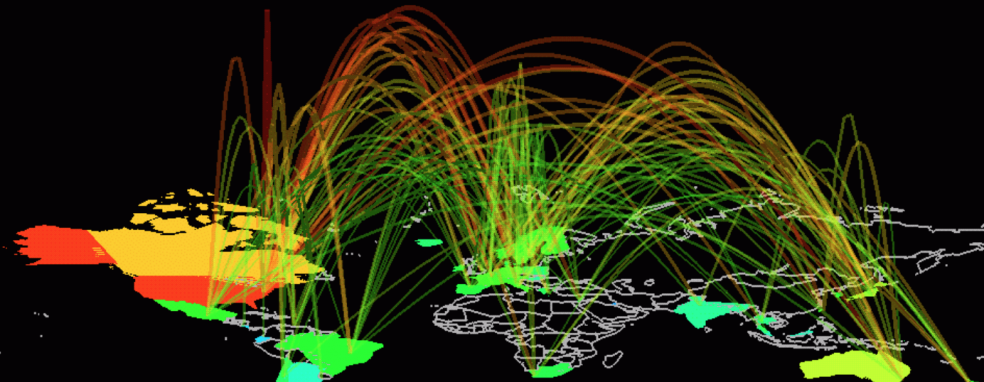

When learners are not limited to learning in classes inside a school, they are distributed in the community. They can interact with others through technologies. This can have significant impact on learning activities. If allowed or enabled by a teacher, learners could be learning from online resources and experts anywhere in the world. Thus, the where of learning changes from the classroom to the world.

Furthermore, the time of learning also changes.

Learners could join different learning communities that involve members from different locations, not necessarily from their own schools. Learners could also participate in learning opportunities provided by other providers in remote locations. Furthermore, learners could create their own learning opportunities by inviting peers and teachers from other locations.

When learners are no longer required to attend class at the same time in the same place, they can have much more autonomy over their own learning. Their learning time expands beyond school time and their learning places can be global.

What to do with this?… As you reflect on Zhao’s thinking on “Where and When to Teach” – use the following questions to assess possible actions…

- What are the practices that I/we should keep? Example: Questioning learners to make connections between in-school and out of school experiences.

- What are the practices that I/we should stop immediately? Example: Restrictions to internet searches

- What should I/we start doing immediately? Example: Offering credit/recognition for out-of-school learning

What’s Next?

What comes next will largely be determined by the responses and feedback toWhat this guide. Was it helpful? What was most helpful? Least helpful? What would you like to see next? We are looking at building a bit of a model for what we’re calling the “Three Learnings Classroom”… a guide for building experieences for learners that offer suggestions for Learning How to Learn, Learning How to Do, and Learning How to Be. Given the growing body of research and experiences with the social and emotional health of our learners, we are especially interested in a focus on the Learning How to Be challenge.

Why Should We Become Involved?

“If those who were not a part of building the reality only consult reality for possibilities, reality will never change.”

“how to be” and our apparent inability to determine who we want to be as a culture/society. The background to this can be found in Clark Aldrich’s book, Unschooling Rules: 55 Ways to Unlearn What We Know About Schools and Rediscover Education. Aldrich suggests that there are 3 types of learning that make up the purpose of school: Helping kids Learn How to Learn; Helping kids Learn How to Do; and, Helping kids Learn How to Be. In this reflection, I’m focusing on the “how to be” purpose.

“how to be” and our apparent inability to determine who we want to be as a culture/society. The background to this can be found in Clark Aldrich’s book, Unschooling Rules: 55 Ways to Unlearn What We Know About Schools and Rediscover Education. Aldrich suggests that there are 3 types of learning that make up the purpose of school: Helping kids Learn How to Learn; Helping kids Learn How to Do; and, Helping kids Learn How to Be. In this reflection, I’m focusing on the “how to be” purpose.  use letters or numbers? Should a 65 be a “D” or an “F” or maybe a “D – “, should we give “zeros”? Why do we use a system that encourages kids to “game” it, to select courses more on GPA implications than by interest, to avoid the risks of exploration?

use letters or numbers? Should a 65 be a “D” or an “F” or maybe a “D – “, should we give “zeros”? Why do we use a system that encourages kids to “game” it, to select courses more on GPA implications than by interest, to avoid the risks of exploration?