Shared from Flickr – CC, Photo by Bo Gao, April 2006

For the past 10 years or so I’ve been working with schools and districts around the country on ways to improve student performance. For most of that time I had the privilege of working with Bill Daggett’s company, the International Center for Leadership and Education. (ICLE). This opportunity brought me into contact with many talented and dedicated people, both at the International Center and in the schools and districts that I had the opportunity to support. One of these people was Ray McNulty. Ray always seemed to capture not only the minds, but also the hearts of the folks with whom he was working.

At one of his presentation, I was reminded of an old TV commercial for an insurance company, where after a grand and flowery introduction extolling the wisdom that the audience would be privileged to receive, the speaker moves to the podium, says the word “Wausau” and walks off. In Ray’s presentation, he did not repeat the ‘Wausau’ moment. But he came close. He walked on stage in front of several thousand people and said, “Culture trumps strategy.”

This past week brought two reminders of the importance of Ray’s statement. The first of these came when I read a blog post from Mark Weston (it’s a great read). He spoke of a recent hiking experience where part way through a challenging trek, he was beset with doubts about his ability to complete the trip. In his words, “ Scared, depleted, no energy to spare, little hope, I seek comfort on a rock. Sitting there, I drink water. Eat four fig bars. Rub my forehead. As I do, doubt keeps me company.”

While there on his rock, exhausted, sore, and dispirited, he heard other hikers on the return trip from his destination. One of he hikers looked at him, smiled and offered, “Nice day to hike.” He challenged himself… if they could do it, so could he. Mark continues on… “From this point on, every hiker I encounter along the final stretch of the trail gets a smile, nod, or kind word—sometimes, all three—from me. I have learned the lesson of this trail. I now see that each gesture, however small, is a conveyance of hope, an antidote to doubt, a soulful balm….”

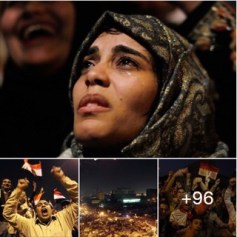

This past weekend I had the opportunity to attend a ceremony honoring the memory of a highly respected and loved superintendent who was tragically killed. He was an inspired and inspirational leader. The ceremony was attended by people from throughout the community. It was a beautiful a testament to the culture of respect and collaboration that he had worked so hard to develop. His former assistant superintendent, now serving in his role, offered the following:

We are gathered here for one single reason — LOVE.

Now hearing this four-letter word can make many of us feel uncomfortable. Although we tend to use this word casually — I love chocolate chip ice cream, I love the Mets… we don’t always know how to say it and use it in the way that we actually live it with our words, actions, and deeds.

Yet over a thousand of us are here because of one man’s love –

- His fierce love for his family

- His love for his friends and his faith.

- His advocacy and love for each student under his care and our work as educators

- His love and steadfast commitment to his community

- And his vibrant love for life.

Boy, did he love life!

Steve taught us that when you see each person and the world with eyes of love, you create opportunities for hope and develop an appreciation for our human connectedness.

This kind of love lifts us so we become our best selves and are able to imagine a world of limitless possibility and potential.

This is not easy.

It takes a conscious effort to live a life of love.

But look how one man’s love compelled all of us to come together at school, in the community, and here today. The love he gave out has been returned exponentially.

Just imagine the power of the collective love of all of us — the way we could transform the world.

For the past 5 years or so, my focus on working with school leaders has been about the notion of culture and the importance of building trust. This is not an easy sell. There are lots of “I/we won’t” statements masquerading as ”I/we can’t” statements.

Cultures take time, sometimes years, to develop. They develop bit by bit. They are not undone overnight. For a school leader, the path is filled with struggles, obstacles, self-doubt. We ask, “Can it really happen? Can I really do it?” By himself, Mark might not have finished the hike. But he discovered he wasn’t alone. In the stillness of his time sitting on the rock and fighting self-doubt, there came an answer.

I learned that Steve would frequently end a short conversation with staff members, students, and his own children with the phrase, “Make someone’s day today.” He did. Kathie’s remarks reveal that they did. You can too.

It’s where culture shift begins.

I recall reading an observation by

I recall reading an observation by

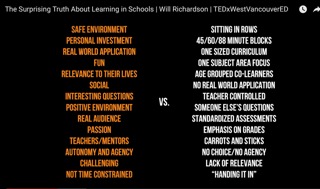

If you do more of what you’re doing, you’ll get more of what yo u got.

If you do more of what you’re doing, you’ll get more of what yo u got.