.Disclaimer: This is not an anti-charter school piece. In my work in the NJ Department of Education and as a consultant for the International Center for Leadership In Education, I have seen both exemplary and horrible charter schools. In the Department of Education my division approved more than a few and closed several. This is about our need as educators to be able to discuss with parents, friends, and colleagues the ways in which new policies can advance or stifle learning opportunities for our children.

For a while now I’ve been following the work of Jan Resseger and have referred to her blog several times here. Jan is a tireless defender of the concept of free public education as the backbone of our democracy and the right of every child to have equitable access to high quality learning opportunities. She has written extensively on the charter school funding issues in her home state of Ohio and, most recently, on the impact of the expansion of privatized, for profit charters in Michigan.

Why should you care about this?

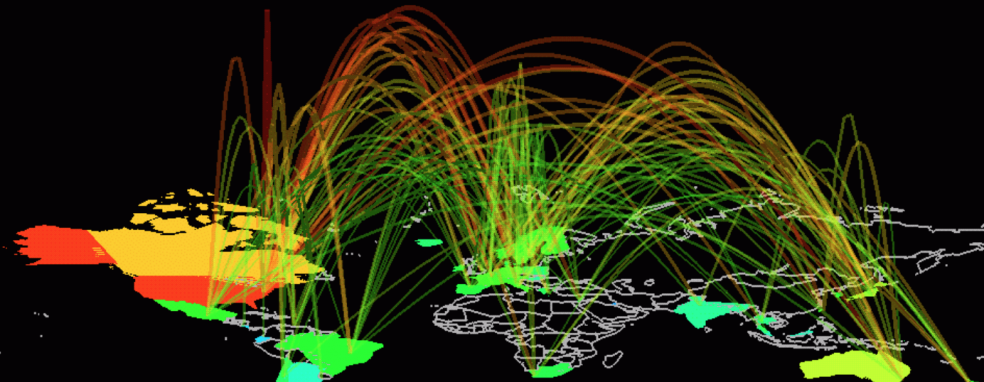

This heavily subsidized agenda is coming to your state, to your town. We’ve seen this movie before. We’ve lived through at least 3 decades of “school reform” driven by the belief that ever more rigorous standards and an increasing reliance on large-scale assessment would be the solution to unsatisfactory student achievement. After all, who would ever argue for lower standards (excuse me for stealing a thought from Ken Robinson)? But did any of us foresee that these reform efforts would develop into 3 decades of No Child Left Behind, the Race to the Top, and the Every Student Succeeds Act?

And here we are again faced with the next great idea… expansion of charter schools, expanded vouchers programs, and re-toolrd versions of school choice. After all, who would argue that all kids shouldn’t have access to a quality school? But this is not about the validity of an idea. Like school reform, it’s about the implementation. It’s about what this idea has that looked like in those states that have been at the forefront of the school choice, charter schools, vouchers, and the privatization movement?

I suspect that many of us have been following the unfolding story of the ways in which our government may be changed as a consequence of the election. One of the more troubling proposed appointments has been that for the position of Secretary of Education, Betsy DeVos.

I first encountered the DeVos family in Jane Mayer’s fascinating book, “Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right”. Mayer is an award winning investigative journalist and has been a staff writer for the New Yorker since 1995. In her book, she describes and documents the ways in which billionaire philanthropists have used their fortunes to advance (aided significantly by the Citizens United decision) their own radically conservative, and often self-serving, agendas. While DeVos has no experience that involves working in public schools, she has extensive experience in promoting the expansion of privatized, for-profit charter schools, vouchers, school choice, and the advance of her very conservative Christian beliefs in publicly funded schools. If you’d like additional background on Betsy DeVos, I recommend a recent New Yorker article by Mayer.

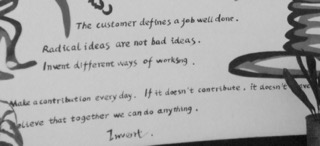

As I have written previously, I believe that this is a time when we, as educators, must become more actively involved in what the future of learning looks like for our children. Most of us can relate stories of having been called upon to explain and/or defend either our profession or the direction of schooling. I write this in the belief that we must become informed and be able to serve as sources of objective and accurate information for our parents, for our community members, and our colleagues. To this end, I urge you to read Jan’s two-part blog on the history and implications of the DeVos appointment. You can read the first piece here and the second piece here. Jan also includes links to a number of her previous pieces that provide fascinating detail about the underbelly of the for-profit charter school business.

I offer the comment section of this blog as a starting point for an exchange of questions and thoughts. I encourage you to take the time to begin a conversation with me, but more importantly, with your fellow educators.