Wow! Did this one lead me down a rabbit hole! Recently, I’ve been drawn to an offshoot of some of my thinking/writing on leadership. In looking at the careers of a number of school leaders (an area with which I’m more familiar than, say, state or federal government), I’ve noticed that, as a nation, we seem to have what Andrew Bacevitch called a messianic complex… a belief in the power of a single individual to solve great problems and to do so quickly and decisively. Bacevitch describes this in his book, The Limits of Power, as a dangerous path, leading to repeated disappointment when the plans/”fixes” of our newly anointed messiah don’t seem to work.

Wow! Did this one lead me down a rabbit hole! Recently, I’ve been drawn to an offshoot of some of my thinking/writing on leadership. In looking at the careers of a number of school leaders (an area with which I’m more familiar than, say, state or federal government), I’ve noticed that, as a nation, we seem to have what Andrew Bacevitch called a messianic complex… a belief in the power of a single individual to solve great problems and to do so quickly and decisively. Bacevitch describes this in his book, The Limits of Power, as a dangerous path, leading to repeated disappointment when the plans/”fixes” of our newly anointed messiah don’t seem to work.

But that doesn’t seem to stop us. One need look no further than the theater surrounding the selection of the next Democratic candidate for the presidency to see this pattern in action. We have grown to value quick, decisive action in our leaders more than we do their ability to thoughtfully analyze situations to uncover root causes – i.e., actually have a chance at solving the problem.

Looking for alternatives to this in my field of interest and experience, I began to look more carefully at the various “solutions” offered during the span of my working years to fix education. I realized that, for a considerable length of time, I had been looking past the blindingly obvious. As often as I had quoted Peter Drucker and Russell Ackoff, I realized that there was a good chance that I had missed the point. You may recall their assertion from earlier posts…

“There is a difference between trying to do things right and doing the right thing.”

In more than 50 years as an educator, I realized that either as a leader or follower, I have been involved in a whole series of education improvement efforts… Outcomes Based Education, Comprehensive Achievement Monitoring, gifted and talented programming for underachievers, values clarification, formative assessment, standards based instruction and grading, soft skill development and assessment, oral proficiency based assessment for world languages, etc. I also realized that almost all of these left no lasting footprints. They came and went with remarkable frequency. They were great examples of trying to do things right (assessment, instruction, learning, etc.) with no attention paid to whether or not they were aimed at the right thing – i.e., they lacked clear, understandable and desirable purpose.

Now I’m standing on the precipice of a rapidly enlarging rabbit hole. Do I just make the point about the critical importance of clear and clearly understood purpose (see Simon Sinek , Dan Pink ) or do I try to see when we lost our way as a means of finding a path back? The rabbit hole loomed.

I couldn’t stop myself. So I went back and explored. I’ll spare you the details (although I can’t resist adding some references in case you can’t help yourself and have to explore a bit more). But here’s the short form.

Prior to the 1890’s the purpose of education was kind of clear… it was for the wealthy the path to maintaining privilege and power. By the late 1800 this was beginning to unravel and, in 1893, The Committee of Ten Sponsored by the NEA (who knew that the NEA even existed in the 1800’s?) developed a plan that greatly expanded education access and included 4 different curricula, greatly liberalizing education in the country. Ironically it was almost 100 years to the month that President Reagan’s National Committee on Excellence in Education released its report on the status of education in the US, A Nation At Risk. It was scathing and got a lot of attention, not to mention that it provided the rationale for the ed reform strategies that we’ve all come to know and love, LOL. But what received little attention was the subtle acceptance of connection between education and the economy which had taken place during the hundred years since the Committee of Ten’s work.

Jumping back from the rabbit hole, we fast forward.

Here we are with a continuing litany of failed “fixes”. And what’s still missing? A clear, understandable and agreed upon sense of purpose.

But what if the problem isn’t that we don’t have “a” purpose but that we have too many. We have purposes that range from custodial (so parents can work) to those that are job skill related (soft skills, 21stcentury skills, etc.). We have purposes that teach social-emotional skills. We have purposes that are academic (get into the best schools). We have purpose after purpose designated as such by those whose interests are best served by selling their particular definition (and often, solultion/s).

How do we know if we’re doing the right thing (vs. doing things right) if we don’t know/agree about what that is? I don’t think we do. What if trying to do the wrong things “righter” just gets us further away from identifying and doing the right thing?

EnterPhoto by Hannah Gullixson on Unsplash

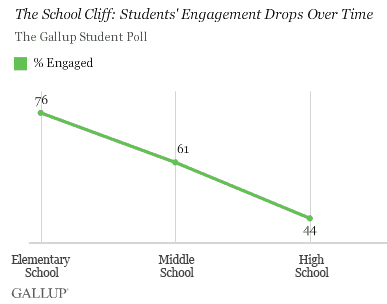

Why should we consider this now? Maybe because we need to reassess what matters. Maybe loading as many kids as possible into AP courses is not the right thing. Maybe eliminating play and recess for kids so that there is more time to “better” prepare kindergartners for the rigors of academic first grade is not the right thing. Couldn’t we at least explore why current student engagement in school learning drops from 80+% in third grade to less than 40% by grade 11?

Maybe putting kids and their parents under significant pressure to attend four years colleges, only to discover that they can find no job in their major but have amassed huge student loan debt is not the right thing. Couldn’t we at least explore why we have increasing studies that document the dramatic rise among our adolescents in stress, anxiety, and depression? In her op ed entitled “We Have Ruined Childhood” published just last week in the New York Times, Kim Brooks offers the following:

“A 2019 study published in the Journal of Abnormal Psychology found that between 2009 and 2017, rates of depression rose by more than 60% among those ages 14 to 17, and 47% among those ages 12 to 13.”

Childadvocates.net

Could we at least consider that we have had a roll in this development? I have no illusions that we will have a conversation about this at the federal level. If we can’t get Congress to return from “summer break” to deal with issues of gun safety, climate change or health care costs, what’s the likelihood of them rushing back to discuss education?

But what if we created the space in our communities for such conversations? What if we tied all future strategic plans to the development of a community consensus about the purpose of education and our schools?

OK, so why am I writing this here? As educators, we blew a chance to help our kids when we were conspicuously silent as our kids were subjected to increasing hours of testing and test preparation… of having their value determined by a test score, of having things like recess, art, music, and electives scrapped, of having important portions of the school budgets cut so that the district could afford the technology required to administer the tests. Oh sure, we eventually spoke up… when the regulations included the use of standardized test results for teacher evaluation. That’s kind of harsh, isn’t it Rich? Yup! But I’m as guilty as anyone, more guilty than many. My offices in the Department of Education approved the standards and designed the specs for the NCLB assessments. I didn’t object. I tried to make them “better”. Talk about the folly of trying to do things right!

But we, many of us as educational leaders, have the chance to move beyond simply doing things right. We have the chance to ask the questions about what the right thing is for our kids. Is it to continue to feed the economy with the workers? Or might it be something greater? What would our school look like if we focused on education as the search for self, or education as the process by which we and our kids seek the road to a good life, a life of empathy, soul, honesty, and wisdom?

What if, right now in our country, we’re looking at the consequences of continued avoidance of these questions? Couldn’t we at least try?

n my introductory post to this series, I shared that I found myself increasingly preoccupied with questions about who we are, who we are becoming, who do we want to be. In this post I’m going to begin that exploration. Today, I’m going to draw heavily on two essays by Charles Eisenstein. Why Charles Eisenstein you might ask (right after “who the hell is he?”)? His essays will give you a pretty good picture. You can read them

n my introductory post to this series, I shared that I found myself increasingly preoccupied with questions about who we are, who we are becoming, who do we want to be. In this post I’m going to begin that exploration. Today, I’m going to draw heavily on two essays by Charles Eisenstein. Why Charles Eisenstein you might ask (right after “who the hell is he?”)? His essays will give you a pretty good picture. You can read them  Today begins a new chapter. I’ve been stuck in a loop. Confronted on an almost daily basis with behaviors and news reporting that treat ratings and factual information with equal value, I’ve had a hard time focusing just on things related to education. What time I found, I’ve been spending participating in an online change school community. It’s been a great experience and most times it has been a welcomed pause from the noise in my head… noise that left me asking big question like who have we become and who do I want to be? But sometimes the distraction of the education conversation isn’t enough. Thankfully. It shouldn’t be enough. As with a growing number of folks, I found myself thinking that if we can’t decide what to call the places where we are housing detained, separated families, we’ve been asking the wrong questions.

Today begins a new chapter. I’ve been stuck in a loop. Confronted on an almost daily basis with behaviors and news reporting that treat ratings and factual information with equal value, I’ve had a hard time focusing just on things related to education. What time I found, I’ve been spending participating in an online change school community. It’s been a great experience and most times it has been a welcomed pause from the noise in my head… noise that left me asking big question like who have we become and who do I want to be? But sometimes the distraction of the education conversation isn’t enough. Thankfully. It shouldn’t be enough. As with a growing number of folks, I found myself thinking that if we can’t decide what to call the places where we are housing detained, separated families, we’ve been asking the wrong questions.

As I‘ve shared previously, Clark Aldrich (Unschooling Rules: 55 Ways To Unlearn What We Know About Schools and Rediscover Education) suggests that there are three critical learnings for kids and, therefore, critical purposes for schools: help kids learn how to learn, help kids learn how to do, and help them learn how to be. Bo Burnham in his highly acclaimed film, Eighth Grade, addresses how hard it is in normal times for a kid to figure out how to be. His character describes her search for “how/who to be” when she’s in the car with her dad, when she sits at lunch with her friends, when she is at a pool party, etc.

As I‘ve shared previously, Clark Aldrich (Unschooling Rules: 55 Ways To Unlearn What We Know About Schools and Rediscover Education) suggests that there are three critical learnings for kids and, therefore, critical purposes for schools: help kids learn how to learn, help kids learn how to do, and help them learn how to be. Bo Burnham in his highly acclaimed film, Eighth Grade, addresses how hard it is in normal times for a kid to figure out how to be. His character describes her search for “how/who to be” when she’s in the car with her dad, when she sits at lunch with her friends, when she is at a pool party, etc.

So, for now, a final dot. What matters to us? What would happen if we decided that a drop of student engagement from almost 80% in 3rdgrade to something less than 45% by 11thgrade mattered to us? Could we ask kids in our school if this is their experience and why?

So, for now, a final dot. What matters to us? What would happen if we decided that a drop of student engagement from almost 80% in 3rdgrade to something less than 45% by 11thgrade mattered to us? Could we ask kids in our school if this is their experience and why? I was reading an article in The Atlantic this morning in which the author described the failure of the Republican party to reject the President’s strategy of using a national emergency as the means to circumvent the Congressional refusal to support his long standing promise of a border wall. The author described this as a “moment of extreme national cowardice.”

I was reading an article in The Atlantic this morning in which the author described the failure of the Republican party to reject the President’s strategy of using a national emergency as the means to circumvent the Congressional refusal to support his long standing promise of a border wall. The author described this as a “moment of extreme national cowardice.” Most of us who taught or who teach now have had a minimum of 16 years as students to learn how school works. While we may/may not have learned everything that was taught, we most certainly learned “schooling”. We learned that “stuff” was organized into discrete content areas, that each of these content areas was taught in fixed blocks of time, that we learned mostly in age-based cohorts, that teachers taught, that tests measured learning, etc. Perhaps most insidiously we learned that compliance was/is more highly valued than questioning.

Most of us who taught or who teach now have had a minimum of 16 years as students to learn how school works. While we may/may not have learned everything that was taught, we most certainly learned “schooling”. We learned that “stuff” was organized into discrete content areas, that each of these content areas was taught in fixed blocks of time, that we learned mostly in age-based cohorts, that teachers taught, that tests measured learning, etc. Perhaps most insidiously we learned that compliance was/is more highly valued than questioning.